Japanese Military “Comfort Women”

- Definition

-

The Japanese Military “Comfort Women” refer to the women who were forcibly conscripted to be sex slaves for the Japanese Army at 'comfort stations' which, under the pretext of the efficient conduction of war, the Japanese Army set up from 1932 when the Shanghai Incident occurred through August 1945 when the Japanese Army lost the Asia-Pacific War.

According to the testimonies of the “Comfort Women” victims, Japanese Army’s soldiers (mostly prisoners), and various official documents and the systems of the Japanese Army regarding the establishment of the comfort stations and the conscription of the “Comfort Women”, the Japanese Military “Comfort Women” were referred to as hostesses, special women, street girls (醜業婦), geishas,, prostitutes, waitresses, etc., as well as the “Comfort Women”. The comfort stations also possessed various titles such as army amusement center, clubs, military service centers, or Joseon restaurants, etc.

- Titles and Characterization

-

Even after the 1990s when the “Comfort Women” issue was publicized, several terms were used to denote the victims who had been forcibly conscripted by the Japanese military to serve as sex slaves for the Japanese military during the Japanese occupation. Each of these terms conveys different value judgments on the issue, and which terms are used holds a particularly significant meaning.

When the issue of the Japanese Military “Comfort Women” was risen up in earnest in the early 1990s, the term 'Korean Women's Volunteer Labour Corps (calling Chongshindae in Korean, 挺身隊)' became widely used. Chongshindae, implying dedication for the nation of Japan (the Japanese emperor), was created by the Japanese Empire to conscript the labor force. Chongshindae, in which women were conscripted as laborers, and the “Comfort Women”, in which women were mobilized as sex slaves, were different in terms of their characteristics. However, the two terms were used interchangeably since the systems and actual operations of Chongshindae and the “Comfort Women” were not clearly distinguishable, as demonstrated by the cases in which the women conscripted for Chongshindae were forcibly taken to work as “Comfort Women”.

Nevertheless, some people raised the need to differentiate those who had been forcibly conscripted to work as laborers from those who had been exploited as sex slaves for the Japanese military. Afterwards, the term was settled on as a result of the 2nd Asian Solidarity Conference on the Issue of Military Sexual Slavery by Japan (1993), which is a solidary comprising of the affected countries that had experienced the damages of the Japanese Military “Comfort Women”. It was decided to use the term Japanese Military “Comfort Women”, which reflected that the Japanese military, the main perpetrator of the crime, was expressly stated and the term comfort women used by the Japanese military was written with quotation marks.

The term "Military Comfort Women”" was also in use in Japan during the 1990s. However, the term 'military' implies that people followed the military of their own volition, as with the cases of 'military correspondent' or 'military nurse'. In other words, one must exercise caution when employing the term, as the term conceals the historical responsibility of Japan which forcibly conscripted the Japanese Military “Comfort Women”.

When the issue of the Japanese Military “Comfort Women” was first raised in the international community, the term “Comfort Women” was used as a result of a direct translation. However, the "Report of the Working Group on the Contemporary Forms of Slavery" (1994)* and the "Report of the Special Rapporteur on violence against women by Coomaraswamy" (1996)** of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights (UNCHR), etc. in the 1990s suggested that the term “military sexual slavery” was more appropriate than the “Comfort Women.”It was because the Japanese Military “Comfort Women” involved a form of "virtual slavery" or "slavery-like practice" in which women were forced to provide sexual services or were sexually abused during wartime. The international community currently uses the term Japanese Military “Comfort Women” interchangeably with the term Japanese military sexual slavery.

- * United Nations Commission on the Human Rights, Report of the Working Group on Contemporary Forms of Slavery for its nineteenth session, E/CN.4/Sub.2/1994/33, 13 Jun. 1994.

- ** United Nations Commission on the Human Rights, Report of the Special Rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences, Ms. Radhika Coomaraswamy, in accordance with the Commission on the Human Rights resolution 1994/45: Report on the mission to the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, the Republic of Korea and Japan on the issue of military sexual slavery in wartime, E/CN.4/1996/53/Add.1 4 Jan. 1996.

As such, the reasons prompting the international community to adopt the term ‘Japanese military sexual slavery’ were that the state (the Japanese government) set up the comfort stations during wartime, forcibly conscripted women to collectively commit sexual violence against them, and the conditions of the female victims' lives resembled those of slaves. When considering the motivation of recruitment, the process of recruitment, and violence involving the Japanese Military “Comfort Women”, the title of Japanese military sexual slavery is seen as more appropriate than the title of “Comfort Women”, which means 'women who provide comfort via consolation'.

Currently, the term Japanese Military “Comfort Women” is more extensively used than the term ”Japanese military sexual slavery” in South Korea. This is because although the term "Comfort Women" is not deemed suitable to accurately reflect the true nature of the issue, it conveys the distinct atmosphere of the period in which the Japanese Empire institutionalized the “Comfort Women” system by coining the term “Comfort Women”. It is also because the title "sex slaves" may remind the surviving “Comfort Women” victims of their pain and lead to further psychological wounds. As a result, the term "Japanese Military ‘Comfort Women’" is also used in laws enacted by the South Korean government to support the victims.

- The Establishment of the Japanese Military “Comfort Stations” and the Scale of Conscription

-

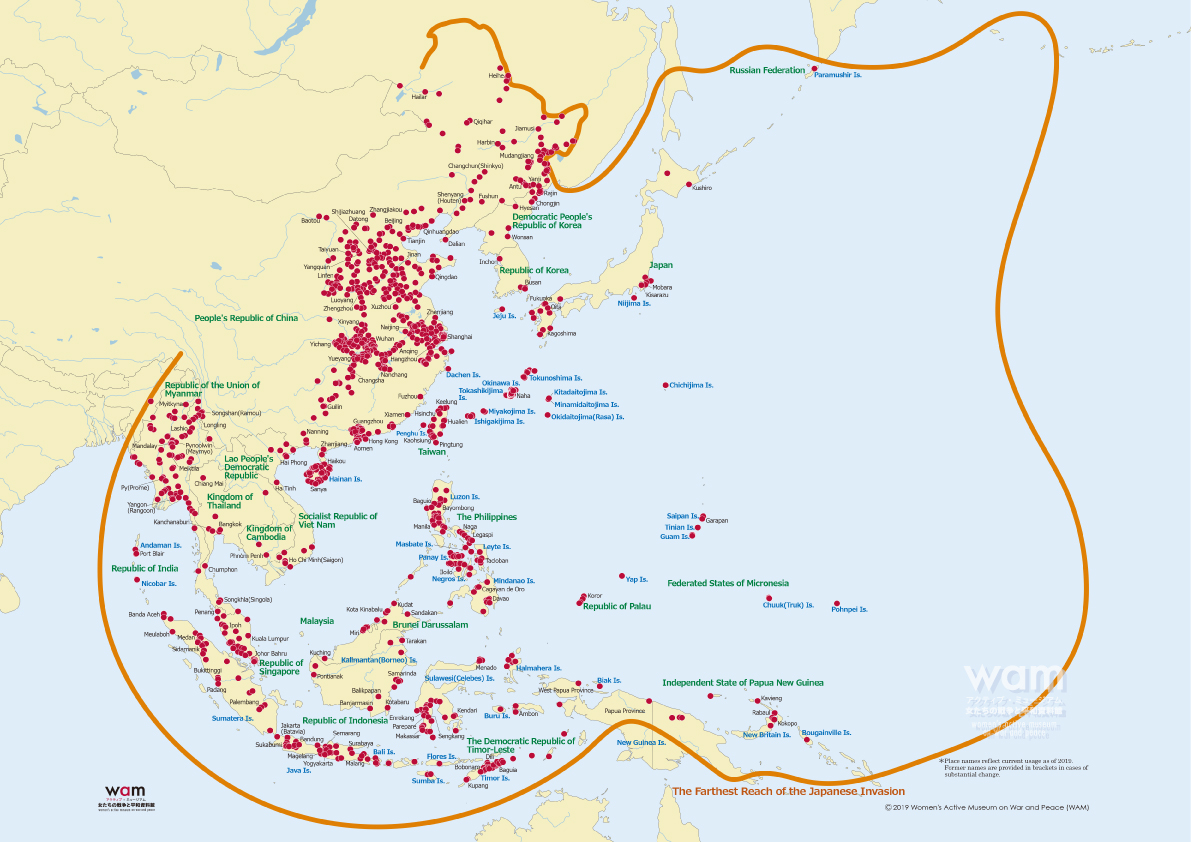

Starting from the Shanghai Incident in 1932 to their defeating in August 1945, Japan built comfort stations in various parts of Asia and the Pacific where the Japanese Army was stationed, including China, Taiwan, the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, Japan, Joseon (Korea), Micronesia, the Solomon Islands, etc. The intention was to effectively carry out the war through preventing the instability of public order caused by sexual violence against local women, containing and managing sexually transmitted diseases among soldiers, and providing sexual 'comfort' to soldiers to boost their morale. In line with this, the Japanese government and the Japanese Army managed and regulated the overall operation of the comfort stations. For example, they systematically set up comfort stations through policies, transported the “Comfort Women” to the battlefield, prepared regulations for the use of the comfort stations, and conducted regular checkups on sexually transmitted diseases for the “Comfort Women”, and so on.

In the early days of the establishment of the comfort stations, women mainly from Japan and the colonies of Japan such as Korea and Taiwan were conscripted as “Comfort Women”. As the war prolonged and Japan's war front broadened ever more, women from other occupied territories of Japan such as China, the Philippines, Vietnam, Indonesia, etc. were also conscripted as “Comfort Women”. As the areas in which the “Comfort Women” were conscripted expanded, the Japanese Army spearheaded all relevant processes ranging from the establishment and management of the comfort stations, to the recruitment and transportation of the “Comfort Women”. The Japanese government agencies, including the Home Ministry, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, etc., as well as the Government-General of Joseon, the Government-General of Taiwan, etc. also adopted a system to facilitate active cooperation.

At present, the total number of women who had been conscripted as the Japanese Military “Comfort Women” is unknown, as the systematic data showing the true number of conscripted “Comfort Women” have yet to be found. Some scholars have even speculated that the total number of Japanese Military “Comfort Women” victims should be based on the data indicating the Japanese Army's plan to allocate "a certain number of “Comfort Women” for a certain number of soldiers" as well as various testimony materials. The estimates of the number of “Comfort Women” vary, ranging from at least 20,000 to up to 400,000 people, and widely differ from researcher to researcher. Yoshimi Yoshiaki (吉見義明), a Japanese researcher who in 1992 discovered and released data revealing the Japanese Army's involvement in the establishment and control of the comfort stations, once published a study that estimated the number of “Comfort Women” to be at least between 80,000 and 200,000. Meanwhile, Chinese scholar Su Zhi Liang (蘇智良) refuted this finding, citing that the number did not include victims in the Chinese region, and claimed that the number of “Comfort Women” ranged between a minimum of 360,000 and a maximum of 410,000, when the comfort stations that had been set up throughout China and the victims in China were taken into consideration.

- Making Voices after half a century

-

Even after the world war II ended, the existence of the comfort stations and the Japanese Military “Comfort Women” has not properly revealed for decades. This is because not only the Japanese government and the Japanese Military failed to prepare any measures to return the “Comfort Women” after being defeated, but they also tried to conceal the existence of the “Comfort Women” rather than officially acknowledging them, and many of the “Comfort Women” victims died in that process. The “Comfort Women” victims who barely survived from the war returned to their home countries or had to find their own way to continue with their lives. It was also not easy for the victims to talk about their experience since the suffering of the Japanese Military “Comfort Women” was perceived to be a shameful past in the patriarchal atmosphere of Asia including Korea. Thus, until the 1990s, the victims had remained silent for nearly half a century in refraining from informing their families and society that they had been the “Comfort Women”. The decisive factor that enabled the “Comfort Women” issue to become socially publicized after half a century was the public testimony on August 14, 1991 given by Kim Hak-sun, who was one of the “Comfort Women” victims. After the testimony of Kim Hak-sun, who shouted, 'Here is living proof', the victim's testimonies and the movement to resolve the Japanese Military “Comfort Women” issue rapidly circulated worldwide.

- Source: Excerpt from The Commission on Verification and Support for the Victims of Forced Conscription under Japanese Colonialism in Korea, Oral records on Japanese Military ‘Comfort Women’ : "Do You Hear? The Story of Twelve Girls".

- The Japanese Military “Comfort Women” Issue as the Agenda for Women's Human Rights and Peacebuilding

-

The victims who gave testimonies about their experiences around the world, as well as the activists and researchers who endeavored to record the victims' testimonies, discover, and interpret relevant documents, and publicize the issue, have called for disclosure of the truth on the Japanese Military “Comfort Women” issue and a just solution to the problem traveling both home and abroad for the past three decades or soand repeatedly. They forged solidarity with the victims from Asian countries which shared similar levels of damage through the <Asian Solidarity Conference on the Issue of the Military Sexual Slavery by Japan>, and sought to publicize and remember the issue through the Wednesday Demonstrations and history education, etc. in a bid to prevent the same event from ever happening again. They also brought the issue to international organizations such as the International Labour Organization and the United Nations, thereby contributing to establishing the Japanese Military “Comfort Women” issue as a women's human rights issue during wartime. In 2000, the victims and the citizens of not only South Korea and North Korea but also Japan, China, Indonesia, the Netherlands, etc. held the <The Women’s International War Crimes Tribunal 2000 for the Trial of the Japanese Military Sexual Slavery> and convicted Emperor Hirohito of being responsible for operating the comfort stations and for mobilizing the “Comfort Women”. Through these Japanese Military “Comfort Women” movements, interest in the Japanese Military “Comfort Women” issue spread worldwide, any illegalities involved in the issue were publicized, and the international standards for solving the issue were established. At the same time, the Japanese Military “Comfort Women” issue has transcended Asia, which had once been a colony or occupied territory of Japan, to become an act of history that should be remembered to promote women's human rights and to build branches of peace.